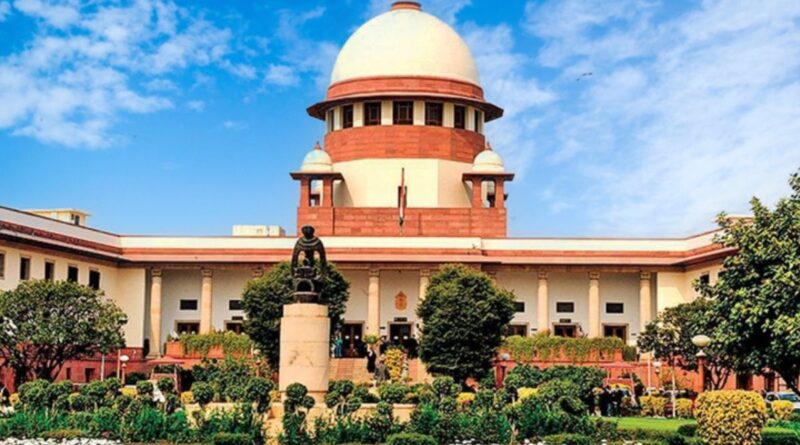

Supreme Court Reserves Judgment on Whether Telecom Spectrum Can Be Treated as an Insolvency Asset

The Supreme Court in State Bank of India v. Union of India & Ors. with connected cases has reserved its verdict in a group of appeals questioning whether telecom spectrum — the radio waves allotted to mobile service providers — can be treated as an asset during insolvency proceedings. The issue arises from the insolvency cases of Aircel and Reliance Communications, where the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) had held that the “right to use” spectrum is an intangible asset of the telecom operator, and therefore can form part of the insolvency or liquidation estate.

The NCLAT had also ruled that the spectrum licence can be transferred during the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) only if the telecom company clears all spectrum-related dues owed to the Government of India.

A Bench of Justice PS Narasimha and Justice Atul Chandurkar heard detailed arguments from the Union of India, the committees of creditors, and the insolvency professionals before reserving its judgment.

Arguments by the Union of India

Attorney General R. Venkataramani, appearing for the Centre, argued that the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) cannot automatically override laws governing the country’s natural resources. His key points were:

- The IBC is primarily a procedural law for managing insolvency, and its overriding provision (Section 238) cannot be used in a blanket manner against other statutes.

- Spectrum is not like coal or oil that gets consumed. Telecom companies only receive permission to use it for providing services; they do not own it.

- Under Section 4 of the Telegraph Act, the Central Government has exclusive control over telecommunication. It grants operational licences, not transferable ownership rights.

- Spectrum remains a natural resource held by the Union as trustee for the public. Since the government owns it, it cannot be counted as the corporate debtor’s asset under Sections 18 and 36 of the IBC.

- He also referred to Article 297 of the Constitution, which deals with natural resources vested in the Union.

- The Attorney General emphasised that if a company enjoys spectrum but fails to clear dues, the public interest must be protected, and the resource cannot be diverted through insolvency proceedings.

Arguments by the Creditors’ Committee (Represented by SBI)

Senior Advocate Rakesh Dwivedi, appearing for the Committee of Creditors via the State Bank of India, took a different view. His major submissions were:

- Spectrum is not a physical resource that can be delivered or stored. The government only regulates its use.

- The “exclusive privilege” under the Telegraph Act means the government can set conditions, but it does not remove the licence-based rights that telecom companies hold.

- When a licence is granted, the telecom operator receives a usable right — a “strand of property” — which is valuable and can form part of the insolvency estate.

- Banks provided massive loans only after signing the Tripartite Agreement with the Government, which assured lenders that the licence could be used as security.

- Therefore, the government cannot later claim it is an unrelated “third party” whose property cannot be touched under Section 18(1)(f) of the IBC.

- He relied on earlier Supreme Court judgments that treated certain developmental rights as assets of the corporate debtor.

- Dwivedi argued that if the licence document does not separately categorise spectrum, it must be treated like any other right granted under the licence and should fall within the IBC framework.

What the NCLAT Had Held

The NCLAT’s ruling, which is now under challenge, stated:

- Spectrum belongs to the nation; the Government only acts as a trustee.

- However, once a telecom operator receives a licence, the “right to use” spectrum becomes the operator’s intangible asset.

- This right can be handled by the resolution professional during CIRP, but it cannot be transferred freely.

- The licence conditions and Tripartite Agreement require that all outstanding dues to the government must be cleared before a licence is transferred.

- A company cannot use CIRP as a way to escape dues or reduce the government’s recovery through the Section 53 waterfall mechanism.

The Supreme Court is now examining whether this approach is legally sustainable.

Case Details

Case: Civil Appeal No. 1810/2021 (and connected matters)

Title: State Bank of India v. Union of India & Others (with connected cases)